|

|

|

Symphony Pro Musica

Program Notes

Robin Hillyard

| Saturday, October 23, 7:30 p.m. |

Hudson

|

| Sunday, October 24, 4 p.m. |

Westborough

|

|

|

|

A Shropshire Lad |

|

|

Violin Concerto No. 1

Marylou Speaker Churchill,

violin |

|

|

Symphony No. 2 |

|

George Butterworth (1885–1916)

Orchestral Rhapsody: 'A Shropshire Lad'

George Butterworth was one of the most promising

English composers at the time of his death in action during the First World War. His total output is rather small,

partly because he concentrated much of his time to collecting folk songs (often with Ralph

Vaughan Williams), and partly because he destroyed several of his early works before setting off for France. George Butterworth was one of the most promising

English composers at the time of his death in action during the First World War. His total output is rather small,

partly because he concentrated much of his time to collecting folk songs (often with Ralph

Vaughan Williams), and partly because he destroyed several of his early works before setting off for France.

Butterworth grew up in fairly comfortable surroundings, studied at Eton and Oxford, then began to teach, compose

and collect. As well as collecting folk songs, he was an enthusiastic and skilled exponent of folk dance, especially

Morris dancing. Immediately on the outbreak of the war, he volunteered with the Durham Light Infantry as a Lieutenant.

He was sent to the front in 1915 and showed great courage quite early on. In July 1916, he was awarded the Military

Cross, almost the highest honor he could receive. A month later, after being recommended for the M.C. a second

time, he was killed leading a raid during the Battle of the Somme.

His output consists mainly of songs and short orchestral works, including three pieces which are based on folk

songs he himself collected. His two major song cycles are settings of poems from A Shropshire Lad by A. E. Housman. The language in these poems is very simple,

but the content is deep, frequently on the subject of young men going to war and failing to return. Such poetry

is ideally suited to musical settings and many English composers were drawn to them, though none perhaps with quite

the success of Butterworth. This orchestral rhapsody which is original, not from the composer's folk song collection,

is based primarily on just one theme from the first cycle - that of Loveliest of Trees, the Cherry......

To quote one of his contemporaries, A Shropshire Lad is his masterpiece, showing singular individual imaginativeness

with great command of orchestral technique: moods at once simple and intense made special appeal to him, and he

expressed them with sensitive intimacy that gives his work a notable place in English music.

|

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Violin Concerto, No. 1 in D major (1917) Op. 19

Andantino – Andante assai; Scherzo: Vivacissimo; Moderato – Allegro moderato – Moderato – Più tranquillo

Although we generally

think of Sergei Prokofiev as being Russian, he was,

like his early teacher Glier, a Ukrainian. Indeed,

he spent only 23 of his 62 years in Russia. He was fascinated by his mother's piano and was able to play well by

the age of six and had already composed his first opera at the ripe old age of nine. By the time he was 13 he had

a portfolio of four operas, two sonatas, a symphony and many other pieces and with these, he successfully applied

to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Not long before his graduation in 1914, when he received the Rubinstein Prize,

he had composed his two piano concertos, partly as school requirements, but mainly as vehicles for him to show

off his own great talent. During the summer, his mother sent him on a short vacation to London, where he had a

chance meeting with Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes, which resulted in a commission for a work. With war

breaking out in August, and conscription starting for the Russian army, Prokofiev was obliged to return to the

Conservatory to avoid being called up. This was a particularly fruitful time in his career, with the Scythian Suite,

the Classical Symphony and this, his first violin concerto. It was the year of the Revolution. In 1918, he set

out on what proved to be a long journey to the United States, via Japan. In amongst his composition activities,

he recorded player piano rolls for the Steinway Duo-Art system. It was also during this period that he met his

future wife, Lina. In 1922, he moved back to Europe, living for most of the next fourteen years in Bavaria, though

he still traveled a lot. Although we generally

think of Sergei Prokofiev as being Russian, he was,

like his early teacher Glier, a Ukrainian. Indeed,

he spent only 23 of his 62 years in Russia. He was fascinated by his mother's piano and was able to play well by

the age of six and had already composed his first opera at the ripe old age of nine. By the time he was 13 he had

a portfolio of four operas, two sonatas, a symphony and many other pieces and with these, he successfully applied

to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Not long before his graduation in 1914, when he received the Rubinstein Prize,

he had composed his two piano concertos, partly as school requirements, but mainly as vehicles for him to show

off his own great talent. During the summer, his mother sent him on a short vacation to London, where he had a

chance meeting with Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes, which resulted in a commission for a work. With war

breaking out in August, and conscription starting for the Russian army, Prokofiev was obliged to return to the

Conservatory to avoid being called up. This was a particularly fruitful time in his career, with the Scythian Suite,

the Classical Symphony and this, his first violin concerto. It was the year of the Revolution. In 1918, he set

out on what proved to be a long journey to the United States, via Japan. In amongst his composition activities,

he recorded player piano rolls for the Steinway Duo-Art system. It was also during this period that he met his

future wife, Lina. In 1922, he moved back to Europe, living for most of the next fourteen years in Bavaria, though

he still traveled a lot.

In his early compositions he rather enjoyed shocking people with his music (perhaps not very difficult during

that ultra-conservative pre-revolutionary period), thus earning himself a reputation of enfant terrible.

And whereas many composers start out relatively conservative in their compositions and develop a more radical style

in later life, Prokofiev reversed this trend (compare, for instance, this concerto and the later one). This was

partly due to his own disillusionment with developments in Western music, and partly due to the political climate

which awaited him on his return to Russia in 1936. For instance, in 1947 he was required to appear, as were Shostakovich

and Khatchaturian, before the Central Committee to defend his "failure to live up to the ideals of Socialist

Realism". During his final six years, his health was quite poor. He died just three hours before Stalin, his

death barely noticed by comparison!

The concerto reverses the normal fast-slow-fast structure of the concerto form. The outer movement are quite

measured in pace. Even the quicker scherzo in the middle has its broader moments. The first movement is a kind

of Russian fairy tale, with themes marked "dreaming" and "narrating". The virtuoso scherzo

is more of a roller-coaster ride, with a kind of drunken peasant march inserted for good measure. The tick-tock

of the last movement is the support for some of Prokofiev's most lyrical writing, though this is quite short-lived

and we are soon dropped back into the fairy tale atmosphere of the first movement.

|

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Symphony No. 2 in D, op. 68 (1878)

Allegro non troppo; Adagio non troppo; Allegretto grazioso (Quasi andantino); Allegro con spirito

The music of Brahms scarcely needs any

introduction – it is as popular today as it was when he was anointed, by his contemporary von Bulow, as

one of the three "Bs" of music: Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. His music is a staple of both the large and

small concert hall, and is loved by performers and listeners alike. But what of the man himself? He did not seek

fame and recognition in the way his New Music School rivals, Liszt and Wagner, did. In fact he led a quiet life,

wanting to be remembered for his music only. Thus he destroyed most of his personal correspondence and tended to

be reticent in large gatherings of people. Only once did he deliberately make his opinion widely known to the public

– the anti-New Music "manifesto" of 1860 – which achieved little other than personal embarrassment. In

short, his life was not the stuff of movies, and most of us know very little about him. The music of Brahms scarcely needs any

introduction – it is as popular today as it was when he was anointed, by his contemporary von Bulow, as

one of the three "Bs" of music: Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. His music is a staple of both the large and

small concert hall, and is loved by performers and listeners alike. But what of the man himself? He did not seek

fame and recognition in the way his New Music School rivals, Liszt and Wagner, did. In fact he led a quiet life,

wanting to be remembered for his music only. Thus he destroyed most of his personal correspondence and tended to

be reticent in large gatherings of people. Only once did he deliberately make his opinion widely known to the public

– the anti-New Music "manifesto" of 1860 – which achieved little other than personal embarrassment. In

short, his life was not the stuff of movies, and most of us know very little about him.

Brahms was, like Mendelssohn, a product of Hamburg in Northern Germany. His father was a musician who played

several instruments in various bands and orchestras, just about managing to make ends meet. His father tried to

teach him his own instruments, starting with the cello and violin, but Johannes was chiefly interested in the piano,

an instrument which, so thought Dad, offered few prospects for earning a decent wage. Fortunately, a local musician

of repute, Otto Cossel, taught and encouraged the boy and allow him to practice at his home (the Brahms family

having no piano). A fortunate appointment as accompanist to the Hungarian violinist Remenyi, and the beginning

of a lifelong association with the violinist Joachim, set him firmly on his way as a composer.

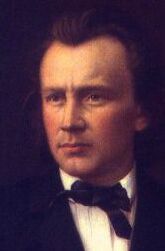

Our image of Brahms is strongly influenced by the photographs from later life, when he was living in

Vienna and hiding behind a full beard. He looks very much the pleasant, grand old man of music, as indeed he was

(at least of non-operatic music). But to understand his effect on people better, we need to visualize him younger

as, for example, when Robert and Clara Schumann first saw him - when he was a handsome, fair-haired youth of twenty.

This portrait of him (right) was painted by Carl Jagerman when Brahms was in his mid-twenties [for whatever reason,

his hair appears quite dark in the portrait, though contemporary accounts claim his hair was still straw-colored

in his early thirties]. Schumann had positively influenced the careers of several young men earlier, none of whom

amounted to much, but when he met Brahms, he was bowled over so completely that he wrote a lengthy article full

of praise, and predicting the ascent of a major musical star. Although it assured the younger man a receptive public,

the article also put him into a mild panic lest he prove unable to live up to his billing. He therefore set to

work studiously improving his technique, and publishing relatively little until he felt ready. Our image of Brahms is strongly influenced by the photographs from later life, when he was living in

Vienna and hiding behind a full beard. He looks very much the pleasant, grand old man of music, as indeed he was

(at least of non-operatic music). But to understand his effect on people better, we need to visualize him younger

as, for example, when Robert and Clara Schumann first saw him - when he was a handsome, fair-haired youth of twenty.

This portrait of him (right) was painted by Carl Jagerman when Brahms was in his mid-twenties [for whatever reason,

his hair appears quite dark in the portrait, though contemporary accounts claim his hair was still straw-colored

in his early thirties]. Schumann had positively influenced the careers of several young men earlier, none of whom

amounted to much, but when he met Brahms, he was bowled over so completely that he wrote a lengthy article full

of praise, and predicting the ascent of a major musical star. Although it assured the younger man a receptive public,

the article also put him into a mild panic lest he prove unable to live up to his billing. He therefore set to

work studiously improving his technique, and publishing relatively little until he felt ready.

The image of Brahms constantly looking over his shoulder at the shadow of Beethoven has been much discussed,

but it is probably the recently "discovered" Bach who had the greatest influence musically speaking.

As in his great predecessor's keyboard music, Brahms makes full use of the equi-tempered scale, with frequent key

modulations through all the sharps and flats (earlier orchestral composers had mainly to content themselves with

easier keys, since early wind instruments were quite restricted in their abilities to play "black note"

passages). Neither did he limit himself to the major and minor keys, as he was quite fond of other modes, too.

However, the music of Brahms is above all melodic and lyric.

Still, it is probably no coincidence that his first major orchestral works were not, strictly speaking, symphonies,

but the D minor piano concerto (which, if you listened to only the first minute or so you might conclude was

a symphony), the lovely German requiem, and the serenades. He clearly wanted to wait until he was really ready

before being compared to Beethoven as a symphonist. The first two symphonies appeared in quick succession, only

a year apart. Brahms was never quite happy with the first, but felt that the second was exactly what he wanted.

The lyrical nature of the D major symphony is immediately apparent from the first measure in the lower strings,

and it never stops. Indeed, the doh-ti-doh of that first measure is a unifying theme of the entire symphony

(all movements are in major keys). The first movement is in 3/4 time and is like a ländler, the peasant dance

of his adopted country Austria and the progenitor of the waltz. A very engaging staccato and pizzicato coda, though

still in the same 3/4 tempo, proves a most apt way to end the seemingly endless flow of melody. The beautiful second

movement is one of Brahms' warmest and richest accomplishments. It begins with one of the great soaring cello lines,

at which Brahms was so good. Two thirds of the way through it develops into a powerful, orgasmic,

climax which leads abruptly back to the tenderness of the opening. The grazioso (gracious) marking

of what is in effect a trio and minuet – note the inversion of the more usual structure here – is the operative

word. It is a lovely, light diversionary piece, a kind of musical sorbet, to prepare us for the rather boisterous

finale. The last movement starts with the sort of theme we expect for a rondò – except that this

time it is presented unison in the strings and is not in the form of a canon at all. The music builds in intensity

throughout, though there are a couple of more tranquil interludes, one which is so Slavonic in nature that it conjures

up visions of Dvorak, another which is a precursor to the opening of Mahler's 1st symphony. The energy increases

until the symphony ends with a spine-tingling D major chord in the trombones.

|

Other Internet Resources

|

Archive of on-line SPM Program Notes

from previous concerts

Return to SPM Concert

Schedule

© This page copyright 1999 by: Robin Hillyard and Symphony Pro Musica.

Please send any comments to:

Robin Hillyard <robin@tiac.net>

Re: SPM Program Notes |

|

updated 16-Oct-1999

|

|