|

|

| Saturday, February 10, 7:30 p.m. |

Hudson

|

| Sunday, February 11, 3:30 p.m. |

Westborough

|

|

MOZART

|

Sinfonia Concertante for oboe, clarinet,

bassoon, and French horn

featuring SPM principal players |

|

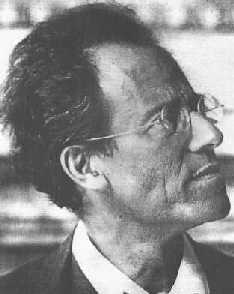

MAHLER

|

Symphony No. 5 |

|

Sinfonia Concertante in Eb K297B (K Anh 9) (1778)

If you were take a poll of

musicians and asked their two favorite composers, chances are many of them would answer Mozart and Mahler. The

brass and percussion players might vary this a little: Mahler and more Mahler. Born approximately 100 years, and

100 miles apart, each of these two masters brought orchestral composition to previously unimagined levels. Each

was significantly responsible for the creation or musical emancipation of many positions in the orchestra: especially

woodwinds in Mozart’s case, and all winds in Mahler’s. Of tonight's program, only the Mahler is truly a Viennese

creation. The Mozart however is a taste of things to come later, during his years in Vienna… If you were take a poll of

musicians and asked their two favorite composers, chances are many of them would answer Mozart and Mahler. The

brass and percussion players might vary this a little: Mahler and more Mahler. Born approximately 100 years, and

100 miles apart, each of these two masters brought orchestral composition to previously unimagined levels. Each

was significantly responsible for the creation or musical emancipation of many positions in the orchestra: especially

woodwinds in Mozart’s case, and all winds in Mahler’s. Of tonight's program, only the Mahler is truly a Viennese

creation. The Mozart however is a taste of things to come later, during his years in Vienna…

The days of traveling around Europe as the child prodigy were

long over. For four and a half years Mozart had, like his father Leopold, been in the service of the Prince-Archbishops

of Salzburg. The position, while offering a steady income, was no match for the musical genius he was and was never

going to lift the Mozart family out of the lower middle class. So in 1777 he resigned his post and left, with his

mother, to seek his fortune. Six months was spent in pre-revolutionary Paris and Versailles, actively seeking a

post. Whereas the Parisian public had idolized the child performer, they did not find the adult composer to their

taste. To add to his troubles, his Mother died during rehearsals for a Concert

Spirituel. The program included the "Paris"

symphony, K297A and was originally to include this Sinfonia

Concertante. Despite being enthusiastically received

by the performers, it was left out of the final program because the director never sent out the parts to be copied.

Possibly, he had been offended in some way by the young composer. When Mozart eventually left Paris in September

1778 without a suitable offer of employment and, in debt, he was obliged to ask his father to intercede for him

with the Salzburg court orchestra.

Today we think of Salzburg as the other musical capital of Austria but, in Mozart’s time, Salzburg was an independent

state, ruled by the Archbishop, one of the loose collection of "German States" resulting from the break-up

of the Holy Roman Empire by the Thirty Years War in 1648. Indeed, the Mozart family considered themselves German, especially

as Leopold himself was originally from Augsburg. It was not until the Congress of Vienna, convened after Napoleon’s defeat

at Waterloo in 1815, that Salzburg joined Austria. Hence, Mozart was as much a foreigner when he later settled

in Vienna as Beethoven and Brahms were after him.

Musically, this period of his life represents a kind of watershed

for Mozart, and the Sinfonia Concertante and the Concerto

for Flute and Harp are typical of it. To put it simply,

Mozart discovered the possibilities afforded by groups of wind instruments. Typical earlier works, such as the

Symphony in G minor

(K183) which frenetically introduces the opening captions to the movie "Amadeus", are, in the Italian

style of the day, almost exclusively string works. Where winds are used, usually oboes and horns, they are ripieno (filling).

The trend out of Bohemia which had taken hold in the palaces and courts of Germany and Austria was the harmonie (small

wind band, typically two oboes, two bassoons and two horns) and was typically used for Tafelmusik (music to

eat by). Mozart was quick to realize the possibilities of such a group in an orchestral setting. A further development

was that of the basset horn and clarinet family (single reed, parallel bore instruments) which had developed to

the point of being playable with equal facility as the oboe. Thus for this piece he took solo oboe, clarinet, bassoon

and horn and added an orchestra of strings, oboes and horns.

It is no exaggeration to say that wind players owe Mozart a

huge debt. Listen, for example, to almost any aria from the Marriage

of Figaro, especially Dove

sono, or to any of the Piano Concertos from about No.

19 on. You will hear exquisite orchestral wind writing of a kind unknown before the year 1778, J.S. Bach’s music

notwithstanding.

The Sinfonia

Concertante is played in three movements: Allegro; Adagio; Andantino con variazioni

(a theme and 10 variations in different tempi, followed by a coda).

Part I: Funeral march – with measured pace, strict, like a cortège

(C# minor); Stormily agitated, with the greatest vehemence (A minor)

Part II: Scherzo – strong, not too quick (D major)

Part III: Adagietto – very slow (F major); Rondo-Finale – (allegro)

(D major)

Mahler’s 5th Symphony is very much "Music from Vienna" although it is very

different from, say, the Strauss waltzes. Vienna, the Imperial capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire for so many

years, has a distinct aura of arrogance, including the sphere of music. Even now, the Opera is proud to exclude

women from its all-male orchestra. A century ago, it was Jews who were excluded from important positions, until

Mahler overwhelmed them with his brilliance as a music director. Vienna was the native city of Schubert and Strauss

as well as the chosen city of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner before Mahler. Why not Prague, Paris,

London, or Milan, all of which had enjoyed great musical traditions? Perhaps there are three answers: first, Vienna

is still, and always has been, at a political and cultural crossroads of Europe: it is where East meets West. Secondly,

music is an integral part of life in that part of central Europe, not just a diversion for the rich, but part of

everyday life for peasants and princes alike. Thirdly, from 1529 when the Hapsburgs repulsed the Ottoman siege,

Vienna had been, relative to the rest of Europe, secure and peaceful. Only a brief invasion by Napoleon, in the

time of Beethoven and Haydn, had disturbed that stability. Mahler’s 5th Symphony is very much "Music from Vienna" although it is very

different from, say, the Strauss waltzes. Vienna, the Imperial capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire for so many

years, has a distinct aura of arrogance, including the sphere of music. Even now, the Opera is proud to exclude

women from its all-male orchestra. A century ago, it was Jews who were excluded from important positions, until

Mahler overwhelmed them with his brilliance as a music director. Vienna was the native city of Schubert and Strauss

as well as the chosen city of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner before Mahler. Why not Prague, Paris,

London, or Milan, all of which had enjoyed great musical traditions? Perhaps there are three answers: first, Vienna

is still, and always has been, at a political and cultural crossroads of Europe: it is where East meets West. Secondly,

music is an integral part of life in that part of central Europe, not just a diversion for the rich, but part of

everyday life for peasants and princes alike. Thirdly, from 1529 when the Hapsburgs repulsed the Ottoman siege,

Vienna had been, relative to the rest of Europe, secure and peaceful. Only a brief invasion by Napoleon, in the

time of Beethoven and Haydn, had disturbed that stability.

Therefore for Mahler, a German speaker born in Austrian-controlled

Bohemia, Vienna was where all musical roads led in 1897. But he was always repelled by the attitudes of the people,

the urban counterparts of those among whom Hitler grew up (born in a small town just eight years previously). There

is a short passage in the second movement, just after a reprise of one of the funeral march themes, where you can

almost hear the jackboots thirty years in the future. "Mahler had this all worked out," according to

Maestro Churchill. This symphony, then, is built on a vast range of emotions, of which a preoccupation with death

and anguish at the injustice of the world, common enough Mahler themes, make up just a part of this great work.

The beautiful Adagietto

is pure love, the finale is hope, and so on. It is this range of emotions which most probably accounts for the

increasingly irresistible relevance of Mahler’s music in our time. But it is his love of life itself that unerringly

reaches us through the music a century later.

One aspect of his music which sets it apart is the orchestration.

The huge orchestra rarely plays with one voice. More often several independent instrumental strands form an intricate

web of contrasting emotions, directions and meanings. There is a passage in the second movement in which two horns

sing a somber melodic line against a cackling motif in the woodwinds. Meanwhile, timpani and basses continue the

funereal beat and the cellos intone a scarcely audible countermelody. As if this weren’t enough, a solo violin

and flute exchange sighs with an English horn. Thus, in a single moment our emotional nerves are tweaked by despair,

longing, aspiration, anguish and tenderness.

Mahler was a romantic and an idealist, striding courageously

into the twentieth century, ridden with doubt and perplexity, ill-at-ease in an unfriendly cosmos. In each of his

symphonies, indeed at every moment of all of them, Mahler seems to be searching for a resolution to conflicts.

Nowhere is this search more fascinatingly dramatized than in the fifth. Composed in 1901-2, it stands at the mid-point

of his career as a composer, holding elements of his earlier and later works in an uneasy balance. During the writing

of the first four ("Wunderhorn") symphonies, he was rarely at a loss for direction or material. Although

he most probably employed a movement left over from the fourth as the basis of the great scherzo, he found that

venturing into less well-known creative territory was harder than expected. "…As if a totally new message

demanded a new technique… It is the sum of all the suffering I have been compelled to endure at the hands of life,"

he wrote. The score of the fifth was heavily revised even after its first performance in Cologne in October 1904.

The symphony is in three parts, with the great scherzo forming

the pivot. Unlike many other symphonies, where the weight of musical expression is in the first movement, in the

fifth, the movements lead up to the summation of the finale. There is also a noticeable forward trend in musical

style. The first part is quite eclectic with its almost constant key modulations, complex counterpoint and orchestration.

The scherzo that comprises the second part, is fairly classical in its construction but its mood is at odds with

its waltz-like movement. The third part is almost totally classical and would not have sounded very strange to

the ears of Beethoven or Brahms. In fact, these later movements draw a significant influence from Bach, whose music

Mahler had been studying at the time.

The first movement begins, like Beethoven’s fifth, with one

of those unforgettable gestures that make an indelible mark on one’s musical memory: a solo trumpet softly intoning

a chilling, doom-laden fanfare during the last rites. And it’s worth noting that the opening recalls the Beethoven

work not only in its suggestion of fate, but in that it employs the same Morse-code like figure. Clearly, not a

coincidence! The music, by turns sad, poignant, violent, oppressive, alternates with a central section in which

the trumpet screams in anguish over a brutally simple accompaniment while the violins lash downwards with a grating

chromatic figure. Every attempt to rise up is dashed. The only real climax is marked klagend (lamenting) and is followed by a long arc of dying against the trumpet

still muttering its fanfare. Against an ominous roll on the bass drum, the procession halts and its burden appears

to be slowly lowered into the ground. The fanfare recedes and the movement ends with a savage punctuation mark,

half defiant yet half hopeless.

In the second movement, which is closely linked to the first,

the mood becomes one of ferocious protest. Snapped chords, grotesque leaps of minor ninths, shrill screams from

the woodwinds, pounding eighth notes, all gestures of overpowering violence, are everywhere. Towards the end of

the movement, the harp makes its first appearance in the symphony and together with the brasses signals a hope

for salvation in a bravely affirmative D-major chorale. But victory’s time has not yet come; the grand proclamation

fades away into terrifying, isolated cries of despair. Yet somehow we know that hope, in its key of D major, will

return again.

The scherzo is on a vast scale compared with the concept as

originated by Beethoven. It consists of an alternation between two very Austrian dance figures: a rather jerky,

grotesque waltz, played a little under the true Viennese tempo and a more bucolic, but nonetheless forceful, Alpine

ländler,

(the slower pre-cursor to the waltz) complete with horns calling from valley to valley.

Like the first part, Part III is comprised of two movements

linked both thematically and by mood. After the exhilarating Scherzo, the famous Adagietto for harp and strings is a haven of peace, full of rapturous yearning

and consolation. For many, this movement, detached as it often is from its context as film score or memorial music,

has come to be seen as an expression of melancholy, full of images of nostalgia, dissolution and decay. Yet, in

its proper place in the symphony, it serves as the perfect transition to the most joyous and exuberant movement

of Mahler’s oeuvre. Mahler’s friend Wilhelm Mengelberg wrote: "this Adagietto was Mahler’s declaration of love to Alma [soon to be his wife]! Instead

of a letter he sent her this in manuscript: no accompanying words. She understood and wrote to him: he should come!!!

Both told me this!".

In a magical transition, the horns and solo winds, playing fragments

of folk-motifs out of which the music to follow will grow, call back the listener from the hesitant inwardness

of the Adagietto

to the radiant, abundant D-major world of the Finale. It is a movement that masterfully combines the forms of sonata,

rondò, and fugue in an exuberant affirmation of the very joy in creation.

Robin Hillyard

(with grateful acknowledgment to Benjamin Zander

for some of the material on Mahler's 5th symphony)

|